Giovanni's Room

Written by Philip Warkander by Michaela WidergrenIn his classic 1956 novel Giovanni’s Room, author James Baldwin at one point describes the relationship between time and the individual. One of the main characters of the novel, the unfortunate Giovanni, tells the narrator of how he experiences the temporal context of human existence, in which all thoughts, deeds and actions are carried out:

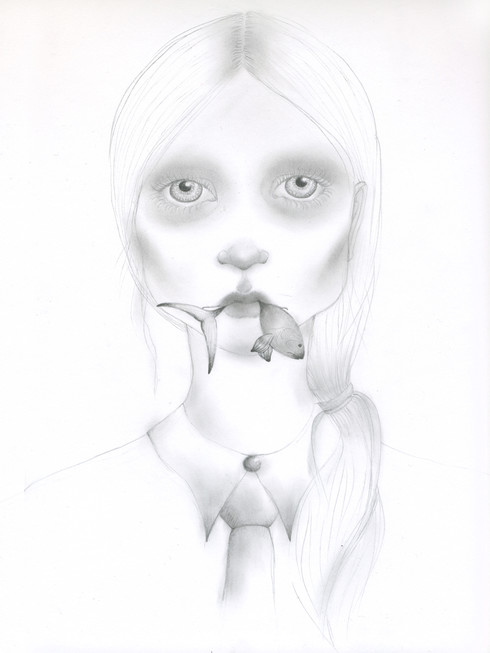

Time is just common, it’s like water for a fish. Everybody’s in this water, nobody gets out of it, or if he does the same thing happens to him that happens to the fish, he dies. And you know what happens in this water, time? The big fish eat the little fish. That’s all. The big fish eat the little fish and the ocean doesn’t care.

For some reason I haven’t been able to stop thinking about this brief passage. In a few sentences, Baldwin has captured the sense of anxiety and powerlessness a person experiences when faced with the seemingly indifference of time; we live, we die, but in a larger perspective, none of it really seems to matter. Our existential traumas, struggles and difficulties which for us are a matter of life or death, is of no relevance to the universe.

Depressing as this may sound, I couldn’t stop thinking about Baldwin’s work, but now focusing on the whole novel, and my reading of it. Originally published in 1956, I read it for the first time in 2012. When I read this text, I see it for the first time, and for me, the text is alive. This way, Baldwin has counteracted the supposed linearity of time and escaped from the demarcations of the indifferent ocean. Through a creative process he has suspended the laws of time, and in a way overcome his own mortality.

A few weeks after I finish reading Baldwin’s short novel concerning events of Paris of the 1950’s, I am in the middle of a new project; Marcel Proust’s In Search for Lost Time. Based (among other places) in the same city as Baldwin’s, Proust’s work spans over several decades, through winding passageways and surprising twists and turns through time, as elaborated by Proust himself. The taste of Madeleine cookies and scent of hawthorn bushes awaken his memory, making him reminisce over times past. Through a deeply personal perspective, he controls the narrative, filling it with detailed descriptions of sexual escapades, romantic infatuations and social ambitions. Long forgotten incidents and people now dead are brought to life, woven into the fabric of Proust’s imagination. Similar to Baldwin, Proust also takes control over time, questioning its linearity and instead molding it into the shape of his own desire.

I read In Search of Lost Time while in Marrakech, Morocco. One morning, I visit Jardin Majorelle, former home of Pierre Bergé and Yves Saint Laurent. The two were deeply fascinated with Proust, and have even named the guest rooms in one of their other homes (Chateau Gabriel, near Deauville, France) after characters in the book.

To an almost extreme extent, YSL was inspired by references from his own life in his fashion design. His passion for art and weakness for Arabic aesthetics (which he discovered through his long stays in Marrakech) were articulated in his collections. This way, his private experiences and personal preferences were materialized in commercial products, to be sold and worn all over the world, by people who had no connection to French art of traditional Moroccan style, thus blind to the references in the garment they wear.

Here, the artistic legacies of Proust and YSL become interlaced. While I read Proust in the former hometown of YSL, I note distinctive similarities in how they operate artistically; using ideas that emanate from subjective and secretive existences, they employ memories and reflections to create a world of their own. This world is open for visits by others, albeit only temporary ones. For Proust, this is carried out through words, while YSL does it literally; designing garments for people to dress up in, wrapping themselves in the worlds of his creation.

This tactic takes us back at the starting point; the relation between individuals and time, and the possibilities of overcoming the contextual demarcations of our existence. Interestingly, both Proust and YSL were physically weak and neurotic, placing them in the category of the smaller fish in Baldwin’s ocean, easy prey for bigger and stronger forces. However, using the power of imagination, they create their own worlds, inventing personal rules and value systems, thus overturning the logic of the mainstream and the ordinary outside of their sphere. Visibly weak but with imaginations stretching outside of the limits of their place in the ocean, they subvert the order of things and, in this way, cheat the logic of time and death.

When I visit Jardin Majorelle YSL has been dead for some time, and his memorial is situated in the garden where I spend my morning, now accessible for the public. But, carrying the Proust-volume in my bag, I have a sense of being able, as Proust did once himself, to edge myself back through time, to when YSL and Bergé were sitting in the garden, engulfed in the stories of Paris past. YSL may be buried here, but his notion of upsetting and tricking time is encoded in the structure of contemporary fashion, thus continually living on through the works of others.