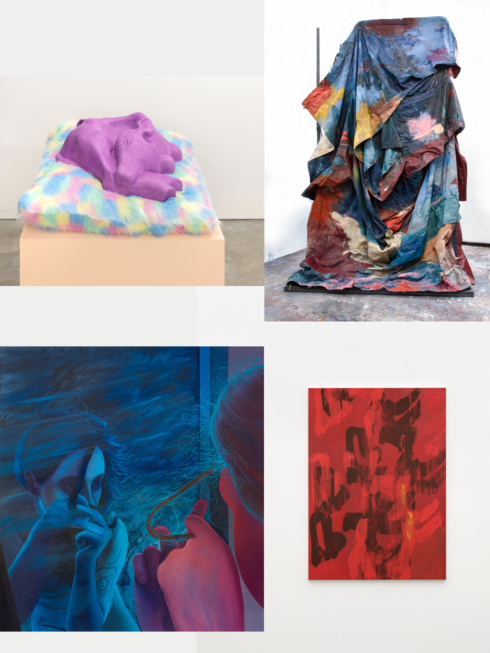

Shi Shi Chi Chi - an exhibition in four acts

Written by Natalia Muntean“Shi Shi Chi Chi” brings together four extraordinary artists, Jala Wahid, Jo Dennis, Paulina Stasik, and Rebecca Lindsmyr, each presenting their work in Stockholm for the first time. Running from March 28 to April 26, 2025, at Belenius Gallery, the show spans painting and sculpture, their practices explore memory, identity, the body, and the boundaries between abstraction and figuration. Though distinct in style, their works share a profound engagement with materiality, time, and layered meaning.

Ahead of the exhibition’s opening, we spoke with the artists about their creative processes, inspirations, and the ideas shaping their new works.

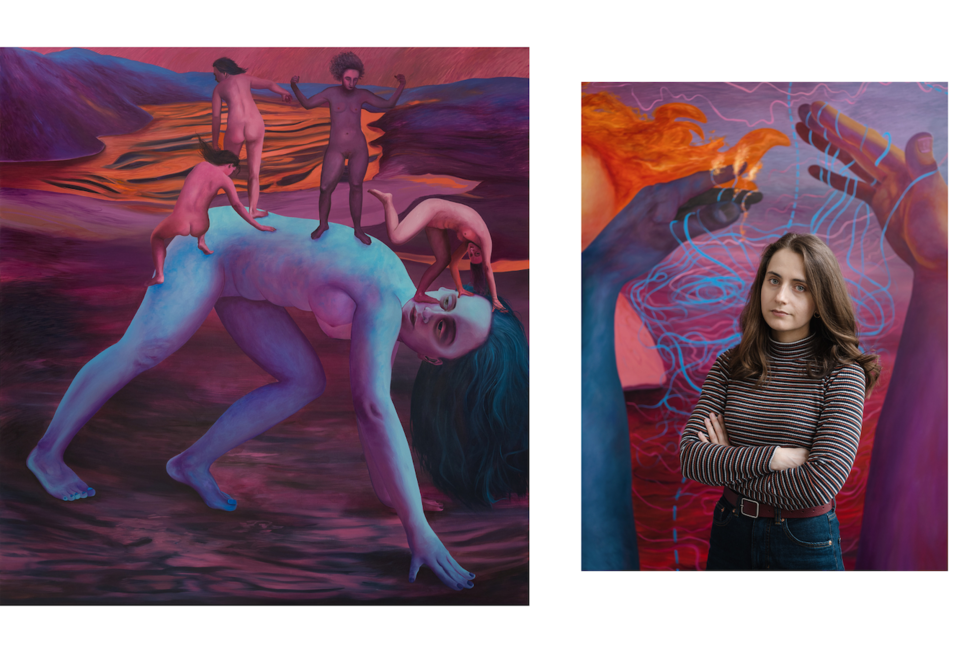

Paulina Stasik - “The body is the primary vessel of emotion - powerful yet impermanent”

Natalia Muntean: Your paintings often depict the female form in various roles and relationships. How do you approach representing femininity and the complexities of female identity in your work?

Paulina Stasik: In my work, women are both the driving force and the ones caught in emotional tensions. I’m fascinated by their complexity—how they can be nurturing and gentle yet strong and independent at the same time. I portray them in shifting roles: mothers, daughters, friends, and rivals, and show how these identities evolve depending on their relationships and circumstances. I deliberately keep them outside of a specific time or place. They exist in a suspended reality, which makes them feel more universal. For me, the personal and the physical are deeply connected across generations - our bodies and emotions carry stories that transcend time.

NM: Your work explores the duality of the body as both a source of strength and a subject of decay. How do you navigate this tension in your paintings?

PS: For me, the body is the primary vessel of emotion. I’m fascinated by its duality - on one hand, it radiates vitality and strength; on the other, it is fragile and vulnerable to the passage of time, change, and pain. In my paintings, I try to capture this delicate balance. I often experiment with the distortion of the figure - multiplying body fragments, cropping silhouettes, elongating or altering their scale. Sometimes the figures are tense, as if caught in a moment just before action; other times, they remain suspended, undefined. This reflects how we perceive our own bodies as something both intimate and unfamiliar, powerful yet impermanent.

NM: Your colour palette is rich and labour-intensive, with layers of red, blue, and purple. How does your process of layering paint contribute to the emotional and thematic depth of your work?

PS: Colour is a vital means of expression for me. It is through colour that I build tension and atmosphere in my paintings. Red and pink evoke corporeality, warmth, and love, but also pain and intense emotions. Shades of blue introduce a sense of coolness, distance, and melancholy. I work in thin layers, gradually applying paint to create depth and subtle tonal transitions. Sometimes, during the painting process, I completely change the initial colour of a piece, following my intuition. I feel as if I have become a captive of these colours, red and blue, contrasting like the extremes of emotion that intertwine in life. I strive to find balance between them, blurring boundaries, allowing one to seamlessly dissolve into the other.

NM: With a strong presence in Poland and internationally, how does your Polish heritage influence your artistic perspective, and do you see your work as part of a broader Eastern European artistic tradition?

PS: In my work, I find echoes of the art of Polish artists, such as Alina Szapocznikow and Maria Pinińska-Bereś, who explored themes of corporeality and femininity in cultural and social contexts. I am also aware of the history of figurative painting in Central and Eastern Europe, its sensitivity to symbolism, metaphor, and a distinctive mood. Polish cultural heritage manifests in my paintings through references to local myths, beliefs, and social narratives. One example is the motif of women’s hair, including a reference to the Polish plait - an old superstition that became part of folk beliefs. In my painting, Bearing the Brunt (2023), I address the theme of intergenerational transmission of experiences. I highlight the fate of women in the Polish countryside, their labour, social constraints, and lack of autonomy. In my work, this theme takes on a symbolic dimension: the house becomes a metaphorical burden under which the woman bends, which can be interpreted as an image of inherited duties and expectations. I draw on history, yet my works are deeply rooted in individual experience. I see my art as an attempt to situate itself within the universal language of painting while maintaining a strong connection to my roots and the cultural context from which I emerge.

Jala Wahid - “I don't bridge cultures - I interrogate systems of power through my inherent perspective”

Natalia Muntean: You work across sculpture, film, sound, and installation. How do you decide which medium best serves a particular idea or concept?

Jala Wahid: It depends on the nature of what I’m looking at and what aspects of it I want to bring attention to. Different mediums offer different ways of working with material, scale and time so often I feel I need all of them at various stages - everything at my disposal! Often, I will develop a period of research into a body of work which works across all of these mediums as I like to interrogate the same material but through different approaches and angles.

NM: How does your Kurdish heritage inform your artistic vision, and do you see your work as a bridge between cultures?

JW: I don’t see my being Kurdish as something that informs my practice, it’s an inherent part of it. What I mean by that is I don’t see it as a separate part of myself that I bring into my work as and when I choose, and so therefore I don’t see my work as bridging cultures because personal histories, identity and lived experience, and the wider political contexts these are rooted in all focus into a single lens - it becomes difficult to isolate any aspect of my intentions or work and attribute to an aspect of my identity. I’m interested in empires, systems and histories of power and authority. The only way I can speak to any of this is through trying to understand my position within this and how I am implicated by this politics, but also, I recognise that these are wider, shared histories, especially when thinking about colonial histories, so it's not possible for me to think about this in terms of 'bridging' cultures.

NM: With recent nominations and international exhibitions, such as the upcoming show at the High Line in NYC, how do these recognitions impact your artistic practice and the themes you explore?

JW: Exhibitions provide me with the opportunity to show in diverse spaces that allow me to assess my approach to making and showing work, especially with regard to how I consider space and scale. It’s essential for me to respond to the nature of a space, what I feel it demands and to decide how I want my work to meet the nature of this space, whether I want it to align with it or to antagonise.

NM: Your work often combines archival research with a visually striking aesthetic. How do you balance the intellectual and sensory aspects of your art to engage the viewer?

JW: For me, the intellectual is sensory and vice versa. What compels me to make work is when I’ve identified an affective/emotive aspect in the subject matter I’m interested in: it’s a demand inherent to whatever I’m scrutinising, but also a demand I make of it, that this is brought attention to. Sometimes what I’m looking at is dense, and difficult to grapple with and decipher and the challenge is processing or distilling whatever I’m looking at into its most essential components to foreground affect without losing crucial elements.

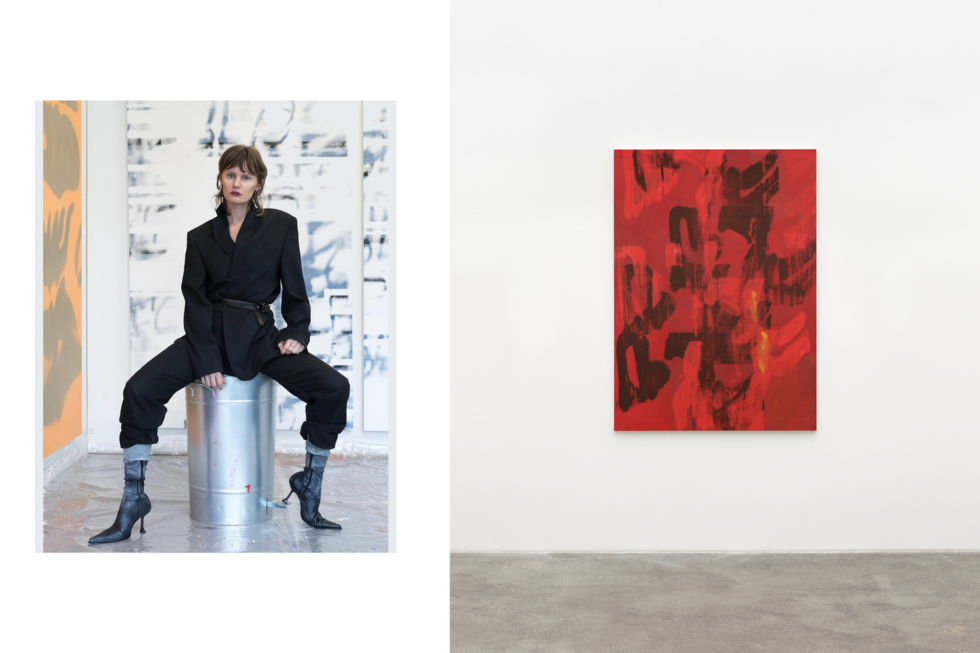

Rebecca Lindsmyr - “My paintings are time and dialogue turned mass”

Natalia Muntean: You’ve been followed by Belenius since 2019. How do you feel your work has evolved since then, and what can we expect from your new pieces in this exhibition?

Rebecca Lindsmyr: In 2019, I was still in a rather early phase of my practice. Since then, my work has gradually shifted. I’ve found ways of getting closer to the core of my interests, trusting the capacities of abstraction and becoming more philosophically grounded. For the group exhibition, which is just about to open at Belenius, I’ll be showing one new painting. It’s a larger and rather complex one; produced through a layered combination of direct and repurposed – screen-printed – gestures.

The gestural is prominent in my work. I’m interested in its relations to subjectivity and readability, to ideas of affectation and aspects of power. A lot is about seeing the expressive gesture in a historical and critical light, pondering how it can be rethought and motivated today; if there’s still something to take from it, or if it has become washed out to a point of muteness. I am currently exploring gestural feedback loops and examining what occurs when a gesture is negotiated and emphasized to the point that it loses recognition as a single entity and instead becomes a mass. How can this mass relate to the establishment or loss of subjectivity?

NM: What inspires your colour palette and the textures in your paintings?

RL: The choice of colour can sprout from associations or come out of a purely visual or material need, such as it being the complementing or contrasting colour to an already exciting one, or picking a colour for its material properties. It might be hard to know if you’re not a painter yourself, but all paints come with their own strengths: different consistencies, transparencies, and weights. As I paint in thin, transparent layers, the choices can also be about how colours mix, and what range one colour morphs into when layered with another. In the studio now, I’m working on a group of paintings. Here, colour becomes something that wanders between the canvases, one choice becomes the motivation for another, and the colours evolve naturally from different needs within the group. As my paints often get diluted through the process, I tend to use quite saturated colours, that gradually lose intensity along the way. At this very moment, I’m focused on depth and darkness, how to keep on bringing blacks back into the work; and how it can survive in the layering without the risk of taking over.

NM: Your process involves building up multiple layers of paint, creating depth and complexity. How does this meticulous approach shape the outcome of your work?

RL: My approach is process-oriented, with a strong focus on painting from the point of layering, both on a material and philosophical level. In the process, I often cover the full surface in semi-transparent coats, which pushes back the previous ones. This way, the painting becomes a body, formed through a gradual build-up, much like an onion. It’s time and dialogue turned mass. The layers allow for a combination of more diligent as well as explosive or destructive aspects. It makes space for investing time in complex processes – both in developing the work and subsequently untangling it as a viewer.

Jo Dennis - “I work until the piece feels like it already belongs in the world”

Natalia Muntean: Your work explores themes of place, memory, and mortality. How do you translate these abstract concepts into tangible forms, whether through painting, sculpture, or installation?

Jo Dennis: My preoccupation with found objects and used surfaces is central to how I incorporate themes of memory and mortality into the works. A found, or used object is, in essence, a physical manifestation of memory. I am constantly looking and photographing the visual language of our built environment, specifically the decay evident in ruinous places and old buildings. I translate this in painting in many ways, by layering, scraping, pouring and also adding various mediums like marble dust, which creates areas of grit and texture. Our built environment is in a constant cycle of decay and regeneration our 'place,' parallels the finite nature of existence, I see it as a reflection of our own mortality.

NM: With a practice spanning two decades, how has your approach to art-making evolved, and what remains constant in your work?

JD: My artistic practice has evolved significantly in terms of materials and focus, but the underlying exploration of the collective and personal unconscious has remained constant. This evolution reflects my ongoing fascination with the complexities of the human psyche and our relationship to the world around us, and my continuing drive to understand and translate my own experience.

NM: What role does intuition play in your creative process, and how do you decide when a painting is finished?

JD: I definitely rely on intuition when I work, and it's an intuition built on years of making. My studio's set up so I'm surrounded by a variety of materials, oil, acrylic and spray paints, old clothing, painting rags and many other used found objects – they're close at hand and, within my line of sight. This way I can work intuitively within a pre-determined set of circumstances, those materials sometimes become a physical part of the work and are conceptually informing the process. I know when a piece is finished because it has a palpable balance, it appears complete to me in such a way that it feels like it already belongs in the world.

NM: What can visitors expect from your new works in this exhibition, and how do they differ from your previous projects?

JD: All three of the works on display are a combination of painted tent fabric and steel. Two of the paintings have a steel framing device, which acts as a kind of architectural intervention, a window or a railing. There is also a sculptural painting which hangs over a steel support. Working with steel is something I have introduced to my practice over the past year, I feel that with these new works and the combination of these materials, it has developed into something very succinct. The viewers can expect emotive works which invite contemplation.

Photos courtesy of the artists and Belenius Gallery