“Feel First, Think Later”: Sally von Rosen on contradictions, her creatures, and the power of objects

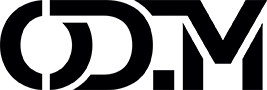

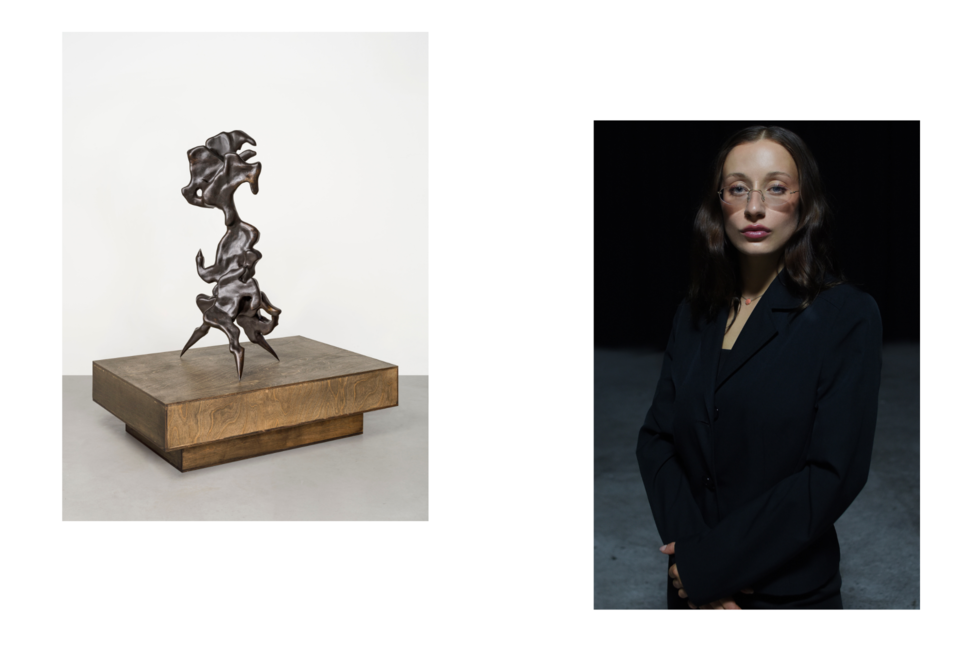

Written by Natalia MunteanSally von Rosen’s work is a study in contradictions - beauty and grotesque, violence and tenderness, familiarity and alienation. Her sculptures, often described as “creatures,” evoke visceral emotions, inviting viewers to feel first, think later. “I want people to experience contradictory emotions,” she says, “to feel both the desire to care for the work and the urge to run away.” Drawing on her background in philosophy and aesthetics, von Rosen explores the political ecology of objects, treating them as active participants in human interactions. “Objects have their own intentions, their own ‘thing power,’” she explains, referencing Jane Bennett’s theories. From her early egg-like forms to her latest bronze sculptures, von Rosen’s work is a continuous evolution, blurring the lines between the past, present, and future.

This ethos is central to the group exhibition Feel First, Think Later at Andréhn-Schiptjenko Gallery in Stockholm, where von Rosen’s hybrid creatures take centre stage. Alongside works by Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff, Dev Dhunsi, and Minh Ngọc Nguyễn, the exhibition explores how intuition and emotion can precede intellectual interpretation. Von Hausswolff’s The Blind Woman (1998) serves as a symbolic portal into the act of letting go and trusting one’s senses, while Dhunsi and Nguyễn examine themes of tension and cultural identity. Together, the artists create a space where materiality and emotion converge, challenging viewers to engage with art on a deeply intuitive level.

From von Rosen’s early egg-like forms to her latest monumental outdoor sculptures, her work is a continuous evolution, blurring the lines between the past, present, and future.

Natalia Muntean: The title Feel First, Think Later comes from one of your quotes about how you want your work to be perceived. Could you expand on this idea and how it ties into the exhibition?

Sally von Rosen: It’s about the transference of emotions - from me spending time with the object to someone else experiencing it in an exhibition. I remember a visitor in 2021 who looked at one of my creatures, the ones with claws and sharp tips, and said, “I want to take care of it, but I also want to run away from it.” That’s exactly the point. It’s about feeling contradictory emotions first, before intellectualising them. Art becomes interesting when it comes from intuition: the shapes, forms, and materials that feel right. Then, of course, there’s theory to apply. I have a background in philosophy and aesthetics, and I grew up surrounded by art - my mother was a ballet dancer, my father was an opera singer, and my grandfather a painter. Art has always been part of my life.

NM: You mentioned the transference of emotion. Can you tell me about your emotions while making Offsprings and Ananke’s Playbunnies?

SvR: These works are part of an evolution. The first ones were like eggs with claws, but they weren’t standing on their tips. At the time, I didn’t think much, I just worked with the material. Later, I realised I made these eggs during a time when my body wasn’t functioning well - I didn’t have my period, and it felt like these eggs were locked in my body. I only realised it a year later when my period returned. These creatures started as eggs, then grew bigger, and I flipped them so they had legs. They started to look more like creatures, part human, part animal. They evolved into a herd, and in 2023, I created a large installation with 60 sculptures climbing on top of each other during Berlin Art Week. The sculptures in Feel First, Think Later refer to that exhibition. My work often evolves in steps, like the evolution of a species. It’s about something that looks like it’s from the future or the past, raising questions about time and existence.

NM: Do these creatures have a life of their own after you create them?

SvR: Yes, once I’ve done my part, they exist on their own, often in exhibitions. This ties into the title Feel First, Think Later. I also research theories that resonate with my work, like Jane Bennett’s Vibrant Matter. She writes about how objects can have their own intentions, their own “thing power.” This idea gives meaning to how I think about my sculptures.

NM: Do you work intuitively, or do you have a plan when creating these creatures? Do connections emerge during the process, or do you start with a clear vision?

SvR: It’s different each time. It often begins with an image - shapes or forms. I start experimenting and realise, “Okay, this means that.” The visual aspect usually comes first, and then I tap into my mental library, thinking about how things relate. It all makes sense in the end. Sometimes, I dig into my foundation, like a “bad archaeologist,” as I once called myself. For example, I made some fragile sculptures that looked like they were sleeping, but the material was strong. I cast them in fibreglass and resin, then broke the mould to get the sculpture out. It’s a violent process, but something beautiful comes out.

NM: It sounds cathartic in a way - hammering it down and then having this newborn, so to speak.

SvR: Sculpting can feel violent sometimes. You have to use a lot of power, especially with certain materials. For example, when I work with bronze, I use heavy tools and a 1000-degree flame to shape the surface. Then I throw acid on it. It’s all very violent and uncomfortable, but something beautiful comes out. It’s interesting how that process works.

NM: Tell me more about you playing with the duality of things. Like beauty and grotesque, or violence and creation? And how do you balance them?

SvR: I think those contradictions are where it gets interesting. How can a sculpture be both of these things? It’s not about balancing them intentionally. It’s about the tension between contradictions, something can be both beautiful and grotesque, familiar and alien. I’m interested in how these contradictions coexist and create meaning. But I believe we don’t need a clear answer. It’s just like that - we have complex emotions.

NM: So you don’t necessarily expect viewers to get a clear answer. You just want to shake up their feelings, to leave them in a kind of limbo?

SvR: Yes. When people encounter the sculptures, it’s nice to hear their interpretations. Someone might say, “I think it looks like this,” or “I was feeling this.” I can’t decide what they should think, and I don’t want to. That’s not art, you know? If I decided that my work is only one thing and that my answer is the right one, I think that’s unfair.

NM: Unfair to the viewer?

SvR: Yes, to the viewer. It’s about giving them an experience, whatever that experience might be. Of course, it starts with me because I made it, but later, it’s not about me anymore. It’s about the meeting between the sculpture and the spectator.

NM: Can you tell me about the titles? Offsprings - I guess it’s because you called them your children?

SvR: Yes, that’s part of it. Offspring can mean children, but in Swedish, if you separate the words - “off” and “spring” - it sounds like something jumping off or springing out of order. And that’s exactly what they’re doing, they’re jumping on top of each other.

NM: And Ananke’s Playbunnies?

SvR: That one is a bit more complicated, a little more existential. The titles sometimes come from what feels right. For Ananke’s Playbunnies, I sculpted them from the silhouette of bunnies, though some people see them as hellhounds or something else. That’s fine, but the shape is from a bunny without the head. Bunnies are also a symbol of fertility, so it all comes together. Ananke is a name from mythology—a Greek primordial goddess of necessity or compulsion. In some stories, she’s the one who gave birth to the cosmos with Chronos, the god of time. She represents the beginning of something big that we’re all part of. There’s also a story somewhere about her and bunnies, which I find funny. The title Playbunnies brings in ideas of necessity and compulsion, and it also plays with the idea of Playboy magazine, joking a bit about human necessities and compulsions. It has a little background in that. These two sculptures link to my earlier work, Main Body, where I had 60 sculptures climbing on top of each other. People often ask, “What are they doing?” Some say they’re in compulsive or sexual positions, or that it’s animalistic. It’s all about human ideas and thoughts coming into play. So the title ties into that and connects to my previous work.

NM: How important is humour in your work, and do you think about it too much or plan it intentionally?

SvR: If humour comes naturally, I invite it into the work. Sometimes, during the process, things look really funny, like sculptures in strange positions, one jumping and another upside down. It’s these unexpected moments that I find great. While I don’t always plan for humour, if it appears and feels necessary or makes sense for the work, I’ll lean into it. For instance, last year, I created a sculpture for an exhibition in Germany at a World War Two bunker with huge ceilings, called Miss Universe. It featured a torso with a butt, a spine, and three legs walking in an extreme, odd way. It was beautiful yet funny, playing with our ideas of beauty and what Miss Universe represents. It’s absurd, but it also comments on body image and societal norms.

NM: So you’re challenging ideas of what’s considered normal or accepted by society?

SvR: Yes, those are questions I find very interesting. I call my works “creatures,” but people project their own interpretations onto them. Sometimes they see an elbow or an animal, and they associate it with vulnerability or something else. One person might say a sculpture looks vulnerable, while another sees it as something completely different. I find that fascinating and it’s a conversation starter.

NM: How do you see your work in dialogue with the other artists in the exhibition at Andréhn-Schiptjenko Gallery?

SvR: The exhibition brings together visual works that evoke emotions first, then thoughts. Even though the visual expressions are different, photography versus bronze sculptures, the common thread is the emotional response. For example, my sculpture stands in front of Annika von Hausswolff’s photograph of a blind woman being led by a dog. There’s a connection there, the woman feeling her way forward, and my sculptures often feel their way into existence.

NM: Can you walk us through your creative process? How do you choose materials or themes?

SvR: It’s an evolving process. For example, I started with Styrofoam, then used fibreglass and resin for larger installations. The material choice depends on the function, and what works for the form. Recently, I’ve been working with bronze, which gives the sculptures weight and durability. I’m now exploring outdoor sculptures, seeing how they interact with different environments.

NM: How does your performance art influence your sculptures?

SvR: Working with Anna Uddenberg taught me a lot about materials and production. Performance art is about being present in the moment, which is different from sculpture. But there’s a relationship between the performer and the sculpture, a connection that I think about a lot. It’s about the interaction between the human body and the sculpture.

NM: How do you see your work evolving in the future?

SvR: I’m currently exploring monumental outdoor sculptures. I want to see how my creatures evolve in different environments. I also have several exhibitions coming up, so it’s a busy year.