Harry Anderson is Bound for Glory

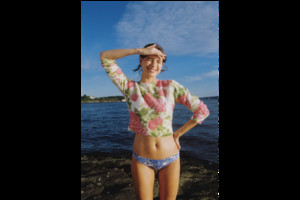

Written by Natalia Muntean“It says Bound for Glory because whenever I want to give up all this, thinking maybe I should do something more stable with my life, my family is always backing me and telling me to just keep on going. So that's for them,” Harry Anderson explains, gesturing to his work Jag är någonting på spåren, mamma (I’m on to something, Mum). The sculpture is part of his latest show, Narrow is the Path, at Saskia Neuman Gallery in Stockholm, on display until February 15th.

Anderson has explored various forms of media, including comic strips created with one of his sisters, painting, and writing a novel Livet är inte alltid Hawaii (Life is not always Hawaii) inspired by his experiences in his twenties. He also engages in embroidery and shares humorous photos on Instagram with another sibling, where they impersonate famous characters or personalities, such as the duo from Absolutely Fabulous or Marina Abramović and Ulay’s encounter at MoMA.

Anderson’s curiosity leads him to unexpected places, weaving personal narratives, symbolic elements, and cultural references into his work. “I walk everywhere and during my walks, I often notice things that catch my attention, and I write them down in my notes. For example, I watched as they emptied the recycling bins - lifting them and opening the bottom so everything just falls out. I found that process really interesting and wrote it down. Other times, it’s about observing people. I might see someone acting in a certain way and start wondering what they’re thinking about.”

Poetry, music and films also serve as sources that feed him with ideas, such being the case with Kaddish, a poem by Allen Ginsberg as a tribute to his mother and her struggles with mental illness. “I love that poem. He wrote it two years after her death, and it’s like a story about her life, but all scrambled together. There’s one part in the poem that focuses on eyes, and the theme of eyes and being watched felt like the perfect connection for this work.”

Reflecting on his creative process, Anderson says, “I know I like to be in control of my work. I think being around fewer people when I create stuff is better for me and for the work.”

Natalia Muntean: Can you elaborate on your liking to be in control of your work?

Harry Anderson: When I'm in the studio and doing my pieces or my art, I'm in total control. It's just me, and that's a really freeing feeling. But the nice thing with ceramics is that I can't have full control, because when I put them in the kiln, with the glaze on, I have no control. You can do a lot of tests like using this clay and this glaze, and it turned out this way. And then I do the exact things again, and it turns completely different.

NM: How is that for you?

HA: It's really nice. I enjoy the unexpected, and also the lack of control. In the early years of my career, when I was painting, there was no moment of surprise. I still love painting and I think I look at painters more than sculptors when I work. But just that element of surprise or lack of control really evokes something in me - just opening the kiln in my studio and seeing all the different ways the sculptures change.

NM: When working on an exhibition, how do you decide which ones to keep?

HA: It’s usually a quick decision. When I’m building a sculpture, I already know if it’s working. If I don’t like the expression on a face, I just take it off and start again. Sometimes I leave pieces I’m unsure about, thinking the glaze might save them. But if I’m stuck, I’ll call friends on FaceTime for their input.

NM: Going back to your beginnings, you studied painting in Copenhagen. How did you make the transition to ceramics?

HA: Yes, and I love painting. I really do. But when I was painting, it was really lonely. I was standing there with myself, painting and listening to music. Every morning, I walked past the ceramics where they were sitting in the ceramic studio, and they all looked like they had a really nice time. They were sitting together, drinking tea, music playing, and chatting. I always thought that seemed so nice. One day, I just popped my head in and asked if I could join. The school wasn't strict, you could do whatever you wanted, so I started with ceramics and thought, this is amazing. In the beginning, I did a lot of vases.

NM: Are you not really okay with being lonely or by yourself?

HA: I know it's like a thin line. Where I'm working now, it's a ceramic studio, so people come in and make things just for fun, for example. They always roll in at about three o'clock in the afternoon, so I get some company for the last few hours, and that is nice. I don't know why, but working with ceramic doesn't feel isolating like painting does.

NM: What does the physicality of working with ceramics give you compared to writing, painting, or embroidery? Why do you think it’s different?

HA: I think the main difference is that I’m building something three-dimensional, so I get to see it from every angle. Also, when you work with clay, you buy it in bulk, like 10 kilos, and then you just take layers off. It’s nice to see how something disappears and something else appears. With painting, it’s just paint tubes everywhere. You can see your work happening, but it feels different.

Now that I’ve been working so long with ceramics, I really like the environment of it. In painting, I also had a lot of other artists to compare myself to, which you should never do. I felt like I was just making bad copies of artists I love, like stealing a tree from one of them and putting it in my painting, so everyone could see it. I don’t know if they actually could, but I could, and that’s what mattered.

But while working for Narrow is the Path, I started painting again at home—just small paintings of my walk home. It’s been about capturing sundown and how the colours change. I’ve been painting a lot of silhouettes of streetlights, street signs, or maybe some rooftops.

NM: How has that been?

HA: Really nice and really hard because I get imposter syndrome when it comes to painting. I don't know why, but I had an idea that towards the end of this show when I was finishing all these sculptures, I wanted to have a painting as a backdrop to one of the sculptures, but it didn't work out. But I think there's something there to work on.

NM: You don't feel the same with sculptures?

HA: No, I don't, and I don't know why. I think it's a comparison thing. There are a lot of great sculptors out there, and I can look at her work and think, I want to do that, but it doesn’t come naturally to me. The same goes for painting; when I look at what I create compared to others, it's different. When I make sculptures, I tend to look at old Greek sculptures or statues of famous people in our environment, for example. One of the sculptures here is inspired by Margareta Krook’s (Swedish actress) sculpture at Dramaten; you can go up to it and put your hand on the stomach, and it's warm. People are drawn to it. Because it’s a real person, I feel it’s strange that everyone takes liberties and gets invasive. If I were to have a sculpture of me that everyone was touching, I would feel weird about it. So that’s why I created my version of her, with a lot of eyes on her head.

NM: Can we talk about “Narrow is the Path”? I know that this is a verse from the Bible, and can you tell me what inspired you to create it? I know it's the pull and push between chaos and structure.

HA: Exactly. I think what inspired me is I've been living a life full of routines. They work perfectly in my working life with the sculptures and creative endeavours. But the question is, how does it work for my personal life, and what does it take from this structured way? What do I miss out on? The narrow path contrasts with the broad way, filled with temptations. I rely on routines because I live my life in extremes—100 or 0 per cent. Without structure, I’d fall into temptations. I now choose what I want to be 100 per cent at, but I can also get really tired of being that way, like a machine. So the inspiration was to take part in my environment - not that I went out to do something I had never done before, but just to open my eyes and my mind to what happens around me. I walk everywhere, and I started to take in my surroundings. For instance, when I walk to my studio during rush hour when everyone is going to work, it feels like I am the only one walking that way while everyone is coming towards me to go to work. That’s why there are a lot of eyes in this piece; eyes are a theme. They represent, perhaps, people looking at me, or me looking at people. I also noticed that birch trees had a bark texture that resembled eyes, so the birch tree looked like an eye watching me. That’s where the form of the eyes originated from. I've also taken inspiration from sculptures on the houses and sidewalks; they always seem to look down at you. It’s not a sense of being watched; it’s just that everyone is there, and everyone has their own life. There are many sprinkled themes in this exhibition.

NM: Was there a moment when breaking the routine brought you something surprising?

HA: It's hard to point out one thing or moment, but I just think the good thing it has brought me is the realisation that everything doesn't have to be this structured. I don't know how long that's going to last, especially now that the exhibition is finished, and I have nothing really to do. But change is good. And for me, it just helped me to realise that everything isn't dangerous.

NM: Did you think that before?

HA: Not dangerous, but like, if my primary instinct is, “I don’t want to do this,” and it’s something normal people do, then maybe it’s something I should do. I can't live on this narrow path, because I know exactly how my life is going to be.

NM: If we can stay on this idea of chaos and structure, how do you manage to express that through the sculptures?

HA: A lot of people see my works as really sad or melancholic, I see them as hopeful. As if they say the worst is over; you don’t know what’s going to happen next. I have a lot of chains in this exhibition, inspired by the chains they use to empty recycling bins and one of the sculptures has a chain in its head. I see that piece as representing the moment when you exhale because it’s been emptied of everything, so it’s a hopeful piece. I called it Som snö i en sommardike (in translation, Snow in a Summer Ditch) because of a phrase I heard in a documentary and it signifies something that’s been left behind, something that shouldn’t be there but still lingers, like snow in a ditch that takes forever to melt in summer. It’s indicative of change. The sculpture itself represents quick change, but the name reflects slow change.

NM: Fascinating where artists’ minds go. I wouldn’t have thought about it like that. But going back to what you said about people seeing sadness in the expressions while you wanted to convey hope…

HA: I quite like talking about my work, but you’ll always have someone who thinks otherwise. And that’s fine. When I look at art, I get a certain feeling. Even if I read the artist’s explanation or hear what it’s about, it doesn’t change my feeling. It doesn’t make it worse or better in any way. People can think what they want. I can explain what the works are about, sure, but I think that’s part of it and it’s fun. I guess people think the sculptures are sad because they look down or seem miserable. I don’t mind; I’m not here to say they’ve got it all wrong. They’re hopeful to me.

NM: Were you always like this when it comes to your work, or—

HA: I think I’ve always been like this but when I first started working with art, there was this idea that you should never explain what your work was about or what inspired it. Maybe 14 years ago, when I saw Karin Mamma Andersson’s exhibition at the Sven-Harrys Konstmuseum called Stargazer. She openly included works from other artists that inspired her. Seeing that was a relief, it felt so refreshing. Being open about her influences made it feel safe in some way.

I’ve always been a storyteller; I tell stories through my work, so I don’t mind talking about them now. If you’d asked me some years ago, I probably would’ve answered differently. But now I believe in involving people instead of excluding them. It’s more fun for both of us if I share those stories and include people in the process. And this is important, not just in art but in life generally. In the last five years, I’ve found it easier to have conversations and to be more open. I think part of that shift is because I realised my work didn’t have a story to talk about before. That created a feeling of exclusion, both for me and the viewer. I think I see myself as someone afraid of conflict but I’ve realised it’s not so bad. The worst thing is, you end up having a tough but meaningful conversation with someone you care about. And that’s still better than avoiding it. Not having those conversations is worse because things just brew over time.

NM: I agree with that. Can you tell me about I Am the Machine Your Parents Warned You About?

HA: Yes, this piece is a perfect example of how my mind works. If we’re tying it to the idea of the narrow path, this routine-based life, it’s humorous and self-critical work. It stems from the phrase, “I’m the guy your parents warned you about,” someone parents wouldn’t want you to end up with. I changed “guy” to “machine” because when I’m working, I feel like a machine: waking up, eating my porridge, going to the gym, staying focused, and not letting anyone in.

So, in a humorous and self-critical way, I thought, “Yeah, this probably isn’t the kind of person a parent would want for you.” But that’s also part of my work: even though the sculptures might look melancholic, there’s humour in some of them. And even though the work feels melancholic, that’s not how I feel, it’s just something I’ve been exploring.

NM: How important is humour for you?

HA: I think it’s important because I just think it’s generally important in life. I’ve seen a lot of Aki Kaurismäki movies. They’re all sad, and melancholic, but there’s a lot of humour in them, and they always end with the lovers together in the end. So it’s a positive ending, and that’s inspiring. You can find the humour in the melancholy.

NM: I can relate to that. I read an interview from 2019 where you mentioned Chet Baker and Amy Winehouse as tragic figures. How do these themes continue to evolve in your current exhibition? Why do you think you’re drawn to melancholic narratives?

HA: I think I’m drawn to it because I can relate to it, and I feel inspired when I listen to that music or watch those movies. I think it’s a part of reality that’s always present. I don’t think it’s about me in my head; it’s more about the way I present myself. I guess I don’t feel sad all the time, but I think that’s interesting.

I don’t listen to jazz that much but what interests me about jazz are the musicians and their lives. They’re good at something, and sometimes they’re excellent, but they often have this downfall. Some people manage to overcome part of it, but some tragically die. I find it inspiring because—well, I don’t know if I’m explaining this well—but life is fragile. I can understand how they get there. I don’t know this personally, but I feel they give a lot of themselves artistically, and people just want more from them. I’m not saying that happens to me, but I understand it.

NM: When you explore themes like tragedy or melancholy, are you revisiting those feelings, or is it a way to distance yourself from them?

HA: Now, it’s more revisiting, but it doesn’t affect me. I don’t take it home with me. I see it as another form of inspiration, like looking at a birch tree. It’s something I can draw from, but I don’t carry it with me. I think that’s good. For me, it’s almost fictionalised. Even if I’m inspired by real events or people, by the time it moves from reality to inspiration, it becomes something between fiction and reality. It’s not something I adapt directly; I just take from it. My inspiration is really wide, it could come from music, movies, literature, or even recycling bins. I think it’s fun to look at things and consider: what if you see it from another perspective?

NM: Do you also draw from personal experiences?

HA: Yes, of course, but I think of everything as buckets. There’s a bucket for personal experiences, one for music, another for books. I take from all the buckets. So, while I have one piece that’s officially a self-portrait, I could name five others that are, in some way, self-portraits too. I’ve sprinkled pieces of myself into all of them.

NM: Can you tell me a bit about mythology and its influence on your work?

HA: There are three that are close to me. I made one of the self-portraits—it’s me, like Medusa. The main element about Medusa is that anyone who looked at her would be petrified. I’ve taken this idea of turning to stone because, as I watch things, I write them down and freeze them in time; this becomes a moment in time for me. The sculptures are ways of capturing memories of inspiration that I’ve frozen in time.

There’s another myth about Leda and the Swan, a story about a really beautiful woman named Leda. Zeus, admiring her beauty, transformed himself into a swan and made love to her. All the sculptures depict them embracing. However, I read a poem by Yeats that describes everything as rape, portraying Leda as a victim. I created a piece called After the Swan, showing a woman turning her head away, all in a black, shiny glaze. There is a swan feather on her shoulder, what’s left of that encounter.

As a child, I remember my grandma had a sculpture called Amor and Psyche. Instead of replicating it, I created a piece with a person and a large shadow behind them. It’s up to the viewer to decide—who is Amor, and who is Psyche?

So that’s how mythology got worked into this. I think about those things, and then I try to think about them some other way.

NM: You mentioned in another interview that you don’t seek perfection in your work. Does this still hold? How does it shape your approach to materials and technique?

HA: For me, perfection is everyone seeing the sculpture and immediately recognising it as anatomically correct. But I don’t approach them that way because I know I can’t create typical perfection. I realise I have my own version of perfection, so I don’t put out just anything. It has to be perfected in some way for me to show it without being embarrassed.

NM: In your novel, you explored the notion of the tortured artist. Did your perspective on this change?

HA: At 20, I felt tortured, but I don’t subscribe to the idea of the tortured artist now. If I were one, I wouldn’t get anything done. The image of a tortured artist requires that inspiration must come, and they have to drop everything and be left alone. That’s not how it is for me. I'm lucky to have inspiration all the time, or if I don’t, I just make something.

NM: Are there any other media or techniques that you’d like to explore?

HA: I’m really into embroidery. After finishing an exhibition, I often feel empty, but ideas come. Back in art school, my teacher encouraged us to explore our ideas and see where they’d go. This feels fresh, and I’m considering incorporating embroidery into my work. I’m not sure how yet, maybe creating backdrop paintings or placing sculptures on embroidered pieces to see how it turns out.

NM: And my last question: what message would you like people to take from Narrow is the Path?

HA: Oh, that’s a hard question, and I haven’t really thought about it. Maybe just that I did a good job. It’s been hard but nice work. Since I see the works as kind of hopeful, I hope they leave with this feeling.

Photos courtesy of the artist, Saskia Neuman Gallery and Carl Henrik Tillberg, portrait taken by Hugh Gordon.