“When You Lose the Heart Behind Your Work, Nothing Works” - How Devon Dejardin Is Weaving His Story

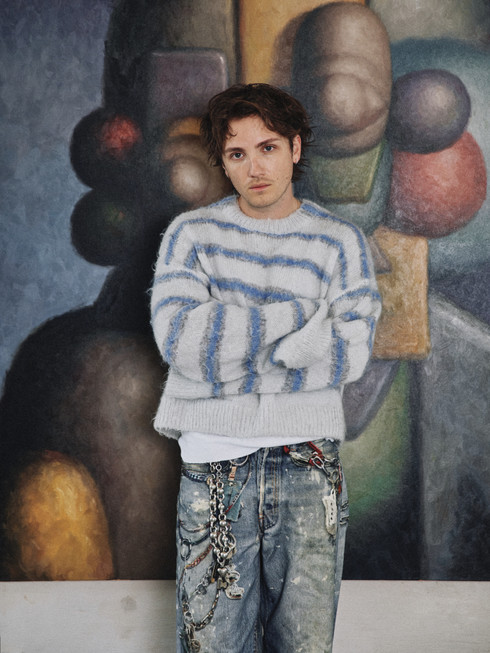

Written by Natalia Muntean“I am intense. But I walk with lightness,” says Devon DeJardin as we stand before Passing Through, his favourite painting from his new show, Pareidolia, and the one he relates to the most. The painting depicts two figures—one receding into the background, in darker hues, and the other leading the way, subtly lighter but still exuding intensity. It's a sort of allegory for the struggles he's been through and left behind, and the self that emerged afterwards. Lighter, but carrying a certain depth.

I met DeJardin right before the vernissage of his first solo show outside of the US, at Hospitalet in Stockholm, and he generously walked me through his paintings. Pareidolia, produced by Carl Kostyäl Gallery and on display between June 12th and July 21st, is the result of five years of exploring the concept of what he calls 'secular guardians.' There is a precision to his art and the human-like figures he paints are made out of geometric shapes, almost floating out of the canvas.

The 30-year-old artist grew up in Portland, influenced by a watercolourist grandmother who often took him to museums as a child. “I didn’t enjoy sitting in museums, but I was exposed to art from an early age, so I became drawn to storytelling and the narratives behind artworks,” he recalls. At 15, he began dabbling in fashion, establishing a T-shirt brand with his business-savvy brother. They won business competitions and expanded into all 50 US states and 16 countries. This venture led to a luxury menswear brand that offered new lessons. “It taught me how to take an object, apply a story and a narrative to it, and then share that with the world. And hopefully, someone will buy it.” However, the fashion industry proved fickle and the brand never really took off, leaving DeJardin to question what it was he truly wanted to do.

Natalia Muntean: Can you tell me more about closing the chapter with menswear and finding your interest in art?

Devon DeJardin: It was a gradual process, slowly losing connection with what I was doing. When you lose the heart behind your work, nothing works. Telling my brother I wanted to step out was tough. We had this brand, and people saw us as “the clothing people,” but I didn't feel connected anymore. So, I stepped out and started bartending in LA right after university to make some money. I worked at top hotels in Los Angeles and got paid well for my age. I loved it, however, it wasn't the environment I wanted long term. I was feeling stuck, discontent, and pressured by student loans. After achieving success with my brand, I found myself living in a one-bedroom flat with three guys, which was humbling and depressing. I realised I needed to make money and considered the corporate world, applying for medical sales positions and recruitment agencies. I got offered a good salary but knew it wasn't for me, so I turned down the job and thought, “I guess I'm stuck bartending.”

At the time, I had about 1,000 Instagram followers and posted some of my clothing stuff. I got a message from an artist in Indiana asking to talk. I was wary, but agreed for $100 for 10 minutes. I took the call while driving to San Diego for a friend's wedding and it ended up being a two-hour conversation. The first thing he asked was if I was spiritual. I replied that it depends. I grew up in a conservative Christian family and studied world religion and theology at university because I wanted to understand everything and not just believe what my parents did. He told me he had been thinking about and praying for me for a couple of years. I was confused because we didn’t know each other. He felt like he was supposed to call me that morning and ask if I had ever painted. I replied that I hadn't, only drawn a bit for the clothing line. So he encouraged me to try painting because he thought it could be good for me. After hanging up, he sent me $100.

Driving back from San Diego, I stopped at a craft store, bought a cheap canvas, paints, and Sharpies, and started drawing on the canvas at my apartment. I didn't know what to do, so I drew shapes and patterns. I sent a picture to the artist and asked if this was it. He said I should keep going. During that process, spending time alone and focused on one thing, I felt a weight lift off me. It became part of my routine. I couldn't afford many canvases, so I used overstock jackets from a clothing brand to create art. I posted my designs on Instagram, and some musicians in LA wanted to buy them. This allowed me to make some money, and I eventually rented an art studio in Hollywood.

Six months after that call, I bought good canvases and paints and started figuring it out. During that time drawing on the jackets, I started making these faces out of shapes because I didn't know how to technically draw a human's face. The shape formation turned into these portrait-style things you see now—very primitive, two-dimensional, no shading, no real colour, just kind of outlines. I made a series of five-foot by six-foot canvases and hung them up on the wall, putting a little story on my Instagram. A friend wanted to buy one for $2,000. His parents, who had a significant art collection, contacted me and bought two pieces for $16,000. Their network saw my work, and demand grew. That moment, six months after that conversation, spiralled everything. Because of them owning the piece, another family wanted to own a piece. And it just started going. I had to take a moment to realise, “Okay, this is something that could really work!”

NM: Was that overwhelming?

DD: It was overwhelming, for sure, because I was painting just to paint and trying to figure out what I wanted to do. I didn't feel I had a story attached to it yet. When it started becoming real, I needed to take a step back. I also needed to make sure that I created a narrative and a story that is true to who I am and what I've learned.

NM: Did you keep any of those first pictures?

DD: I kept a couple. I like to maintain a few works from each year to remind myself of certain things. In my studio in Los Angeles, I often show visitors what I'm working on, and the originals so they can see and understand the progression.

NM: You said that after you made that first sketch, you sent a picture to your friend Zach, the artist who called you. Why did you feel the need to do that?

DD: I did it because of the conversation I had with him and my experiences travelling and studying different religions. His tone and voice had an authority that made me feel he should be part of my journey. I'm open to connecting with people who feel significant to my path. I wasn't trying to get anything from him but wanted to keep him updated since he started me on this journey. We've been great friends for years now, and I'm one of his groomsmen at his wedding in September. He was an early mentor who knew a lot about art and encouraged me to explore and discuss it.

NM: It feels like the origin story you told me had so many right people at the right time. Do you believe in serendipity?

DD: Oh, for sure! I call them divine moments. You really understand your own story when you look back. Reflecting on my journey, even back to university, I noticed some moments that seemed to happen outside of time and space, and they resonate universally, beyond just religion. I think these moments are always happening, but many people don’t acknowledge or lean into them. They miss these moments because they might seem peculiar or uncomfortable. Random people played significant roles in my story because I was open to them. I've come to believe that important moments often come when you're nervous or anxious. My story involves being comfortable with the uncomfortable and trying to stay there. This isn't easy, especially with mental health struggles like anxiety, which has always been a challenge for me. I have panic disorder, where my heartbeat races and I feel like I can’t breathe. When that happens now, I see it as a sign that I’m where I’m supposed to be because something important is about to happen. I try to reframe it that way.

NM: So you stay in that moment - that's courageous! How has your work evolved over eight years? Were there moments where you changed your technique?

DD: Many artists, including myself, face the “what's next?” question. I've stayed with similar imagery for the last four to five years, with some smaller exhibitions in different styles, but all cohesive in the narrative. My technique evolves naturally, without any drastic changes. I'm not going left field here and right field there and this and that. I treat my studio practice like a nine-to-five job. I am a product of routine and routine for me produces results and progression. Because I can paint a circle every day for the rest of my life. But the circle I started with when I was 10 years old compared to what it looks like when I'm 100 years old, is naturally going to be so different. My current show might look similar to past work, but it feels different. There's no massive stylistic shift, but technical details change, like adding colours to make something feel more rounded. My style progression comes from a consistent battle of applying myself day in and day out.

NM: Can you describe a day at your studio? You said it's a nine-to-five job, but do you have any rituals?

DD: A typical day starts with a morning routine of coffee and stretching. I then drive to pick up my assistant, Richie. Funnily enough, he is an assistant who can’t drive, but also a close friend and someone who understands my work and travels with me a lot. So those 30 minutes when I drive to pick him up, I get to stay silent in my car with no music and think about the day ahead. I reflect on what I did yesterday and plan what I want to achieve today. And then, by the time I pick him up, I feel like I have a clearer, articulate plan of what I've been thinking about. And then for the next 30 minutes, as we drive to the studio, I'm able to process everything with Richie. So it almost feels like he is some sort of a therapist. Once we arrive at the studio with a plan, Richie sets things up. And then I'm able to work silently. Sometimes we play music and talk and laugh. I usually try to keep a light atmosphere in my studio, but there are also moments and times when we have to be a little more serious. Art for me is such therapy. It’s this beautiful moment filled with light and even on the worst days, just being in the studio, in that environment, even if I don't feel like painting, makes me feel better.

NM: You mentioned that even on bad days, you go into your studio, how do you overcome artistic blocks?

DD: I think I'm still trying to learn it. I wish there was a golden button, you could press to figure out what that is. I think that the best way for me to get over an artistic block is to just keep going at it. Because even if I just sit and stare at a wall for days in a row, at some point, as long as you're committing to being there, something will come. And for me, I feel like art is a lifelong commitment. And if you try to escape something that you feel called to especially when it comes to art, it'll haunt you. So show up, and interact with it! Not every day is going to be great, but there will be days that are major triumphs. Other things help me, such as running, going to the gym, having good food and being around communities. Art can be isolating so I believe it's extremely important for artists to be surrounded by other creative people, and also people who might have less exciting careers that they are happy with. It allows you to understand differences in this world.

NM: Do you start by standing in front of a blank canvas? How do you begin?

DD: Usually, for an exhibition, the process involves a couple of months of planning out not only the story and the narrative but also how it's going to be presented. I always start with literature, either writing or researching to find a topic that resonates with me. Much of my work deals with different worldviews. So maybe it's reading a book that analyses a certain text from the Bible, the Quran, or a Buddhist text. You find one or two lines that really affect you, then you delve into different texts that analyse that phrase. From there, I look at my past work to see how I can apply my style and narratives from prior exhibitions to create something new. It's a process of picking, pulling, replacing, and reconfiguring. Once I have a bright idea, I go into a sketching process, creating loose-form sketches to see which configurations could work for a painting. At that point, I might have 30 or 40 different ideas, from which I select the best 10 to 12. I arrange them, thinking about how each painting can interact with others to create a new overarching story. This process draws from my fashion background of creating mood boards. Then, I transfer the drawings to digital form, often using iPads and computers because creating a rough draft digitally is much faster than making small paintings. These digital drafts are printed and arranged on a wall, much like a mood board. Then, I start painting, using the references I've created. Everything that comes before the painting is crucial; the painting itself is the extension of that captured moment.

NM: Speaking of themes and motifs, I read this description of your art in an interview: “he uses art to explore the delicate dance between darkness and light that is the human experience.” Can you elaborate on that?

DD: Darkness and light are major themes in all my work. The way light hits these figures is a beautiful moment, and the most challenging part is fine-tuning it. I'm not painting people or landscapes; it all comes from understanding how light reflects off objects. It's not just about light and dark; it's about how humans experience them—dark moments, triumphs, love, grace, repentance. Our journey here is constantly experiencing pain and joy. We can't escape them, much like anxiety or depression; we've all had low moments. When I hit my lowest, I wanted to give up. But there's this moment where you see a flicker of hope, a voice urging to hold on. Climbing out of that dark pit made me understand the importance of dark moments because light cannot exist without darkness. People tend to favour one over the other, but both are necessary to balance our lives. Although it is uncomfortable, nine times out of ten it's actually very easy to defeat the darkness in our lives. But we don't always allow ourselves to stand in front of that shadow, to face that moment because it’s scary.

NM: Do you think it's about defeating or befriending the shadow?

DD: Personally, I feel like we should defeat this stuff that's holding us back, but I also think if I could describe it like an image, it's shaking hands, putting it behind you, allowing it to stay there as you move forward. There's this biblical story everyone's heard, David and Goliath and I find it interesting because David, a shepherd, goes out with his sling against Goliath, known as the most savage warrior. Goliath, nine feet tall, challenges David, but when David walks down to face him, Goliath says, “Come to me, you small person” because his gigantism affects his vision and coordination and he can't see well. If you strip it apart, this Goliath in front of you seems like the most undefeatable challenging oppressor out there, and David, young, afraid, and seemingly unlikely to win, faces him with confidence. And it's this beautiful moment of understanding life and this symbolic way of the giants or the darkness ahead of us. Most of the time, it isn't what it seems. And if we just confront it, and stand in front of it, we're probably going to be able to knock it down.

NM: You mentioned a voice that guided you to hold on in your darkest moments. Whose voice was that?

DD: It was something beyond me. You can say God, but labelling it as God can lead to various interpretations. I believe we all have guardian figures in our lives, regardless of our beliefs. These guardians can be humans, deities, benevolent spirits, or even animals like pets. They help us, whether we are religious, spiritual, agnostic, or atheist. We all have this innate desire to want something in this world to help us along, and I think that that resonates differently in every single person. When you allow yourself to be open for those things to speak, they'll come to you when you need them.

NM: Were you always open to these kinds of experiences?

DD: I don’t think so. The hardest part when you're in your roughest moments is to want to be open. Especially after you tried talking to people, or you read books, thinking it's going to help you and without getting any relief. That was my story. And then came this kind of moment of complete defeat, mixed with a feeling of release, of calm. That's when I realised I was going to be alright. And I also think, letting go is sometimes great. But it's not the case for everyone.

NM: I absolutely relate to this! Can you tell me a bit about this exhibition, Pareidolia, and the Guardians? What are they? And who are they protecting?

DD: I called the show Pareidolia, which is this disorder that humans have to make imagery and familiar shapes and forms out of things that are not necessarily true. So pareidolia would be seeing Jesus’ face in a piece of French toast, for example. It's a way our psyche works to process unfamiliar information by creating recognisable images. The term “pareidolia” has Greek origins, meaning “beyond shape and form.” I love the concept of looking beyond simple shape configurations to uncover deeper meanings. Some people see human portraits in my work, others see animals, and some perceive angelic, guardian-like figures. And for me, that's the perfect version of what we talked about, of these guardian figures in our life that can be humans, animals or deities. I am just trying to find a way to paint and blend them.

Also going into pre-Arabian deities, in pre-Arabic religions there was no language or imagery to describe divine encounters, so they used stacked stones to symbolise gods and angels. They resembled these kinds of outside-of-time and space figures. And then in the Arctic indigenous tribes, when they set off to travel through different lands, they would leave stacked rocks as guiding points for people to follow and let them know they're in the right spot. My work is a lot about blending various moments of protection and guidance from different religions, creating a concrete and identifiable image that symbolises protection and that can be applied to any context you choose.

Pareidolia features a lot of doubles, and they are always in motion, confronting each other, overlapping, or looking back at one another, representing both protection and self-reflection. For instance, one figure might be well-lit, symbolising a benevolent spirit that's there to overlook and make sure that it's this moment of clarity, while the other might be shadowed, reflecting a past trauma or challenge. As they interact and move through each other, they symbolise growth and the journey through personal experiences. As if to say, “We were once even. And we had this conversation, but now I've moved through you. And you're back there.” Does that make sense?

NM: It makes total sense!

DD: So this whole exhibition, as I said, is about coming in front of moments that you need to face that people don't want to face.

NM: How do you measure success? What is success for you?

DD: I've been asked this question, and it changes every single time because I think success changes as you grow. For me right now, success means balance, and balance in the sense of balance within yourself, your friendships, your family, and others, and being able to have a non-egotistical life that is lived through service and generosity. If you try to describe success in a monetary value, it's just never going to work because the most successful people on paper that I know are also the most depressed ones. I feel most alive when everyone around me, including myself, feels balanced.

NM: What is one question about your art that you would like to be asked?

DD: Wow! Okay, this is gonna sound so generic, because it's kind of what you've already asked, but it's a deeper inflection, I guess, on it. I want someone to ask me what it means, but I want them to ask me that in 50 years. At that point, I want to be able to really give people a full story of how every piece and every exhibition tells a certain chapter of this ultimate story. Through each exhibition and the way I archive and document my work, I plan to weave these narratives into a long-format story. Each exhibition I do, I see it as a chapter of that longer story.

NM: Do you know the ending of the story?

DD: Yes, for sure. It's gonna be cool. But also it might be left open because I might not be able to finish it, but hopefully, I will get to finish it.