The Sound of the Walls

Written by Art EditorLast chance to catch “The Silence” - a video work by artist Amie Siegel at ArkDes in Stockholm. The piece was commissioned by ArkDes for an exhibition on architect Sigurd Lewerentz previously this year. When our art editor Lina Aastrup met with Siegel and her musical collaborator Jeff Murcko in Stockholm in June, they were in the final phases of installing the work which is still on show until October 30.

The Sound of the Walls - A conversation with Amie Siegel about translating architecture, music and silence.

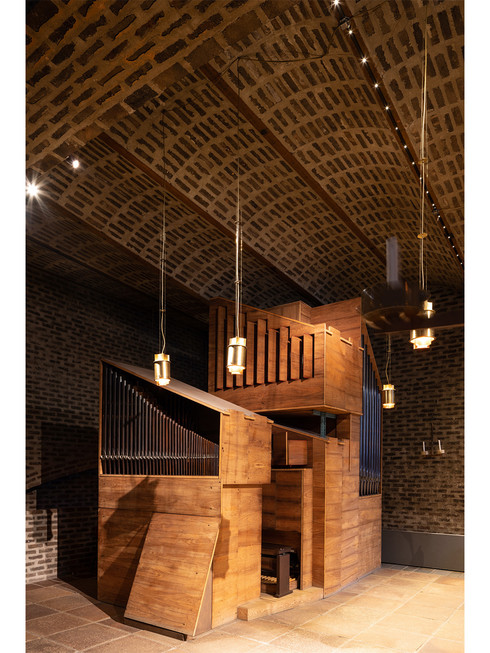

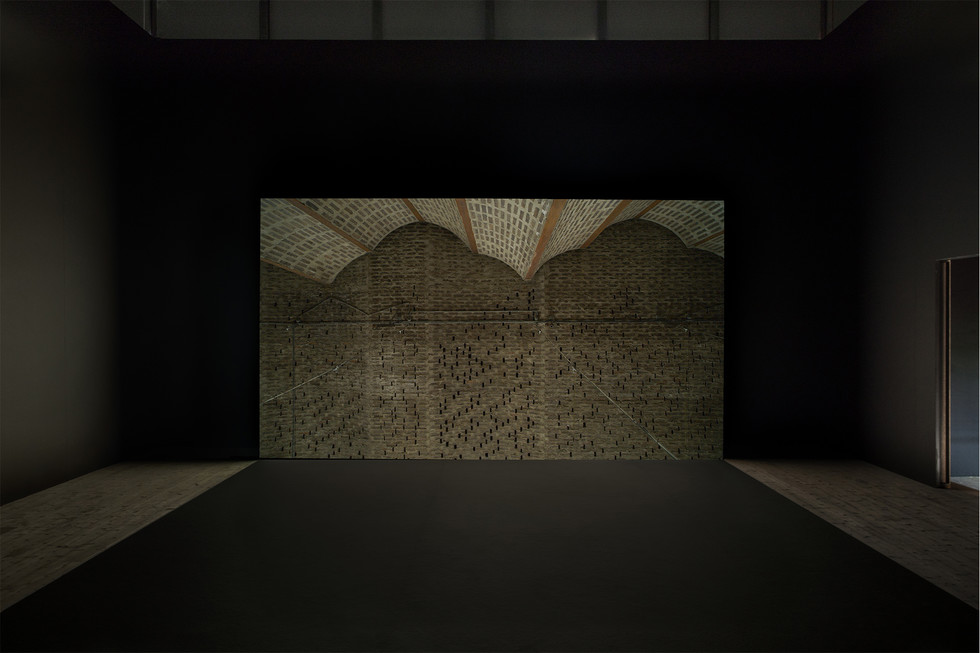

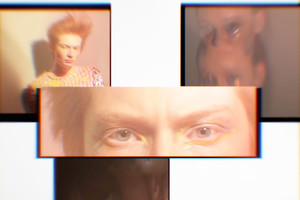

Lamps suspended like singular notes hang floating in mid-air. Square gaps in a brick wall. The camera slowly moves from left to right, like it is reading a music score. Siegel lifts the image and audience, readers and listeners up up up – high in the air beneath the vaulted ceiling with its beautiful arches. We hear music coming from the organ – an odd hybrid between melody and atonality, undefinable yet enjoyable. Its regular syntax dissolved and recreated into a new language.

Lina Aastrup: As an artist, you work with many different mediums. What about this work made you choose this particular medium?

Amie Siegel: I visited a large number of buildings that Lewerentz designed, and I was most interested in St. Marks in Björkhagen, Stockholm and St. Peters in Klippan. In each of those churches there is this amazing brick work where certain bricks were left out creating gaps in the walls. It seemed very clear to me, looking from the walls of the churches to the organs – that Lewerentz also designed specifically for each church and which are very different from a normal organ – that there was something to do with rhythm and music that I wanted to make even more present. It wasn’t so much creating musical scores from the walls, but rather that the walls were already scores and our work was to translate them into sound and have them played by the organist in each church.

The final work is a double channel video projection. Since the scores come from the walls of the churches, it was important that the projection was made not on screens but on walls that have been erected on opposite sides of the exhibition space. The projections alternate, like a call-and-response in a church congregation. This way, each church would have its own space and film, but they would together be the whole artwork. You can’t see one without the other.

Jeff Murcko: Call-and-response is common in some churches like the American Baptist church for example, but it is also a musical term. Here we have a visual call-and-response situation which is also reflected in the audio.

AS: I have made other pieces on celluloid film, and works that are sculpture, installation, assembly, photographic or performance based – but the medium always depends on the idea that drives the work. I think certain artists identify themselves by their medium, but I do not. Very importantly. I am interested in how we culturally associate certain ideas with mediums and then using those ideas to bring out our predisposition to them. Celluloid film for example is often associated with nostalgia, or paint with the luxury art market for example. So, as an artist I could never solely be engaged by one medium.

LA: I listened to another interview with you where you called yourself a “medium-slut”.

AS: Yes, I stand by that still. But it’s not a one-night-stand, it is a long-term engagement with everyone, with all of them.

LA: Why deprive yourself?

AS: Exactly, of all these things you can have pleasure in. The metaphor that keeps going - haha.

LA: In your work “Provenance” (2013) you look at the art market system – is this work a similar take on the religious system or the church as an institution?

AS: I understand why you would ask that question, but no, not at all. I didn’t look at the churches as religious spaces so much as spiritual spaces. Even more importantly, as spaces that are dedicated to abstract ideas that engage us in terms of our belief systems. And they deal most importantly with the immaterial, and the immaterial is everything like a belief system, and music. Because music, while it evidences itself in instruments and our voices and so forth, is immaterial as far as a medium. It doesn’t have a screen, it doesn’t have paint, it doesn’t have marble. It’s completely immaterial, so in a way there is a space that sound and music engage that feels similar to a belief in something that is not always making itself known to you. Or isn’t there. This reminded me of the God’s Silence trilogy by Ingmar Bergman where there was always a character struggling with God’s silence.* This inspired me to think about musical scores as giving, not a voice, but a musical presence to something outside and beyond of ourselves.

LA: In terms of process, how did you go about writing and ultimately translating these musical scores from the walls into the final work?

AS: The basic impetus of the project was to hear what I felt were embedded scores in the church architecture. And how the different churches had their different scores. So as far as process, after that it was mainly a matter of being able to decipher the score and this is where I collaborated with Jeff. What key should be it in, should it sit along the keyboard of the organ, should we do it so that it is playable by a human, and how should it take form, which cord should be assigned to which etc? So, the translation involves a level of interpretation of course. When the scores were finished, we gave them to the organists who then further interpreted them as musicians. It was important to us that they bring their own individual mode of playing. Each church only has one main organist, so they have a strong connection to their instrument. They know them well; they play them almost every week or every day even.

JM: One of the most important aspects of the scores were the pauses since they correspond to the architecture.

AS: Where the pattern stops and it continues only a little but later is where the pauses in the score is, so it was important that that got represented as it reflects the architecture. That the silent spaces are as important as the musical spaces.

LA: So, you could say that the formal aspects of the work resonates with the architecture?

JM: Yes, the spaces in the two churches that determined the note value are very different. The marks and gaps are constructed differently. St. Peters is made up of longer slats and St. Marks is very square, making one feel legato the other more staccato. Of course, to someone else they might appear differently or be interpreted differently, but to us this felt like the most logical way of reading the architecture.

LA: Why work with churches at all when the religious aspect was not the main subject of the piece?

AS: When I am looking for spaces for the work I do, I am interested in the program of the space. I ask what the space is for and whether there is something in the architecture that is reflected in there. For example, there is a piece I did that is quite connected to this work called “Double Negative” (2015). It was filmed outside of Paris in the Villa Savoye by Le Corbusier, and in a copy of this building in Australia. The original building is all white and the copy is black. The original building’s program was a residence but it is now a museum onto itself, a national monument of France. Whereas the copy was designed as the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies – an Ethnographic research institute that also holds within it a vast collection of films, audio recordings and visual material related to indigenous cultures within the Torres Strait islands. This connection is what makes it interesting - why there would be a copy of a dominant, canonical, Western male architectural work in the other hemisphere?

LA: So, you take a sociological perspective on the building?

AS: Yes, but the works are also sound, and image driven – they are not merely documents or reportages. They are highly thought through, rigorous formal works where each choice around the image and the sound suggests something meaningful towards those concerns. My interest isn’t necessarily in architecture or in churches, ethnography or modernism – it’s in how they come together in these very strange ways and what that says about us culturally.

Amie Siegel (Chicago, b. 1974) lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. She is internationally renowned for her multilayered, meticulously constructed works that investigate value systems, cultural ownership and image-making. Siegel is represented by Thomas Dane Gallery.

*The God’s Silence trilogy consists of “Såsom i en spegel” (“Through a Glass Darkly”), 1961; “Nattvardsgästerna” (“Winter Light”), 1963; “Tystnaden” (“The Silence”), 1963.