Stockholm Art Week: An Interview With Mark Frygell

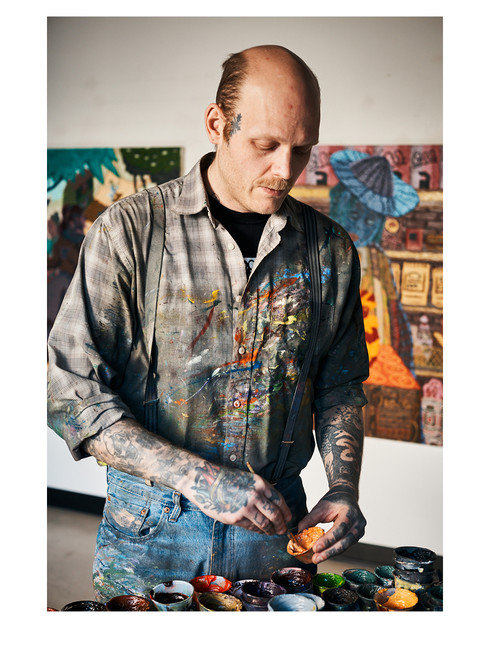

Written by Natalia Muntean by Zohra VanlerbergheMark Frygell’s art thrives in the liminal space between the grotesque and the playful, where ambiguity sparks open-ended narratives. Born in Umeå’s punk scene and shaped by years as a tattooist, his paintings, vibrant, textured, and teeming with surreal characters, invite viewers into a world where fantasy collides with the uncanny. From Renaissance graffiti to surreal memes, his influences are as eclectic as his output: a testament to a practice driven by curiosity rather than convention.

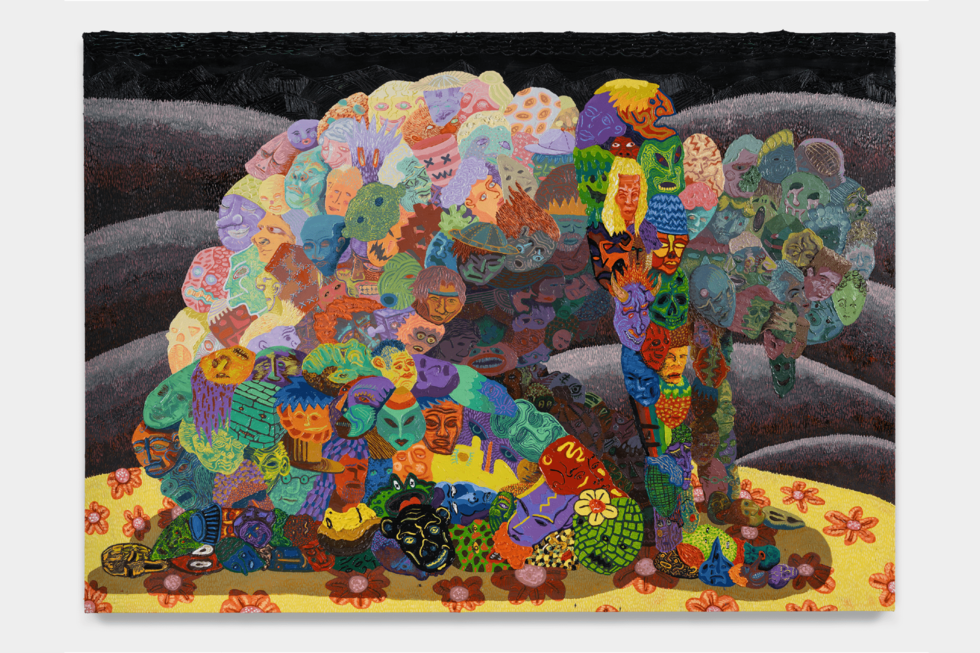

Natalia Muntean: Your work often blends the grotesque with the playful, exploring ambiguity and fantasy. How do you approach creating these contrasting elements, and what do you hope viewers take away from your art?

Mark Frygell: I hope that what the viewer is taking away is very subjective. To a large extent, when you grow as an artist, you drift further and further away from designing an artwork to have a certain effect on the world and, instead, the outcome of your process becomes something you trust the viewer will find its way in relationship to. Nowadays, we are so used to having things packaged and served to us and, in that sense, artistic work is more important than ever to break that habit and help us see things for what they are. It’s a “shields down” kind of approach, I suppose.

In the studio, I am most interested in experimenting and discovering where it leads and what the outcome might be. Then, of course, I have my background, taste and hang-ups that colour the aesthetics of what I do. I rarely think too conceptually about what a piece should be or what is good or bad, a failure or a success. Curiosity and interest in the medium, whichever that is, are what drive me to the studio every day.

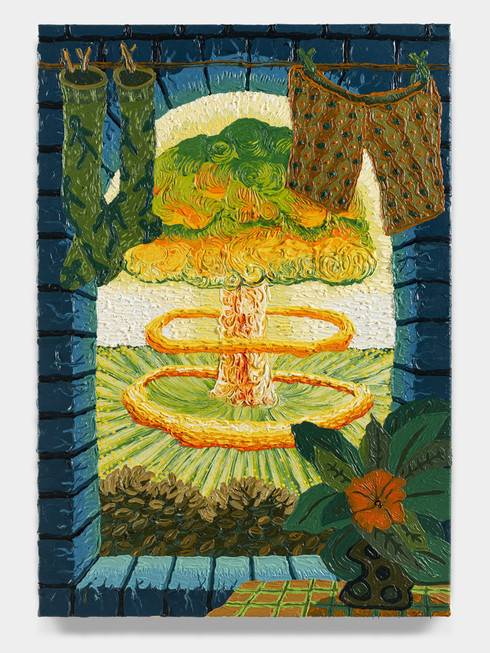

I have some sort of obsession with the imaginative and grotesque that colour my work, not as an intention but more as a consequence. I have thought about it a lot and there is something in it that feels transgressive and limitless. Ever since I was a kid, I have had a huge interest in the wonky, weird, and odd. From Garbage Pail Kids and Weirdo Comics to underground roleplaying game illustrations, renaissance graffiti, the Neue Sachlichkeit of the early 20th century, and even the surreal memes created by teenagers in Blender, I am drawn to unconventional forms of expression.

A couple of years ago, I discovered that the word “grotesque” originates from “grotto-esque,” an aesthetic trend from 15th-century Italy. This trend started when a farmer fell through a hole and found a hidden festive building built by Emperor Nero, with walls adorned by surreal paintings of plants, animals, and humans. Initially, these images were seen as strange and fantastical, but over time, the word began to take on a negative connotation of “ugly,” influenced by conservative views seeking to uphold the status quo.

NM: Growing up in Umeå’s alternative music scene and working as a tattoo artist, how have these diverse experiences influenced your artistic style and multidisciplinary approach?

MF: It has shaped everything I do! One of the advantages of being part of the alternative music scene is its small size, which encourages participation. This creates an environment that is very supportive of creativity. Even if you’re young and inexperienced, you receive a lot of encouragement to explore your talents. As far as tattoos go, I think it has coloured my work less. When I started working professionally with tattooingvaround 2011, the “wild style” was quite new, and adopting a more artistic approach was an interesting way to work. In that sense, the art coloured the tattooing more than the other way around.

Around 2015, I was also very lucky to become friends with Emil Särelind (Frogmagik) of Deepwood Tattoo in Stockholm. He had studied at Konstfack and was very dedicated to working in a similar vein. It was an interesting time when most other studios focused on traditional tattoos, while the entire scene began to feel stale. He played a significant role in shaping the tattoo landscape in Sweden that we have today, particularly by consistently inviting tattoo artists with similar ideas from all over the world for the past 10 years.

NM: During your residency with the Mack Art Foundation in NYC, how did the city and its art scene influence your creative process, and what was the most memorable part of that experience?

MF: It’s an amazing city, very inspirational, and many people are extremely dedicated to what they are doing in a way that just boosts your creativity. I spent a lot of time walking around all over Brooklyn, Manhattan and Long Island. This is my favourite thing to do in general when I am travelling. You see so much and a new interesting discovery is just a corner away. Of course, it is a luxury to be able to see amazing art shows, alternative music scenes and all the awesome food but it all pales in comparison to just exploring the streets in a city of this magnitude. It maintains its universe somehow.

Mack Art is also a fantastic residency that was so supportive and made my day-to-day life and work very easy. Christine who runs it is a super active person who just makes things happen.

NM: You’re collaborating with A Day’s March and have a unique relationship with clothing. How does fashion intersect with your art, and what can we expect from this collaboration?

MF: I have a terrible fashion sense myself. Most of the time I just dress in things I have stumbled upon. I don’t really go shopping, and I think most of my clothes are basically memorabilia from my travels, printed shirts that friends have made, and sportswear because it’s comfortable. Plus, I tend to mess up my clothes with paint and stuff anyway.

With that said, I love looking at people and how they express themselves, and in my paintings I like to come up with clothes for my characters that are unconventional and don’t necessarily fit with a specific time or place.

When A Day’s March approached me to collaborate, I got excited to just work on material that is not what I am used to. I wanted to see how the clothes I painted would look. In that sense, it’s almost like documenting a process. To be honest, some of the clothes look pretty rough and remind me of my early attempts at making band shirts in high school. However, I kind of like that aesthetic, maybe for nostalgic reasons. I hope when the work is done it will have a big range of looks and it will be visible that they are made in a basement studio by hand and not printed in a shop to have a unified “look”.

NM: Storytelling is central to your work. What narratives or themes are you currently exploring in your work, and what will you be presenting during Stockholm Art Week?

MF: The truth is, I have no idea. I’m just creating and seeing where it takes me. I think storytelling is central, but more as a container for images than as a way to tell a story. I like that feeling from when you were a kid, unable to read, looking through comic books and trying to decipher a story, even though it all felt kind of blurry somehow. Sometimes as an adult, I can get a similar feeling when I encounter art from a culture I’m not familiar with. You can see that there’s a lot of significance and many narratives but you are blocked from reaching them. I find that a very fascinating place to be in, and I try to have the same relationship with my work. If I know exactly what something is and what it communicates, I feel like it’s dead and a failure once I’m finished. I need some space left in a work to keep my brain active and engaged with what I’m looking at. A good story is not an explanation or a vessel for meaning, it’s a collaboration between maker and viewer.