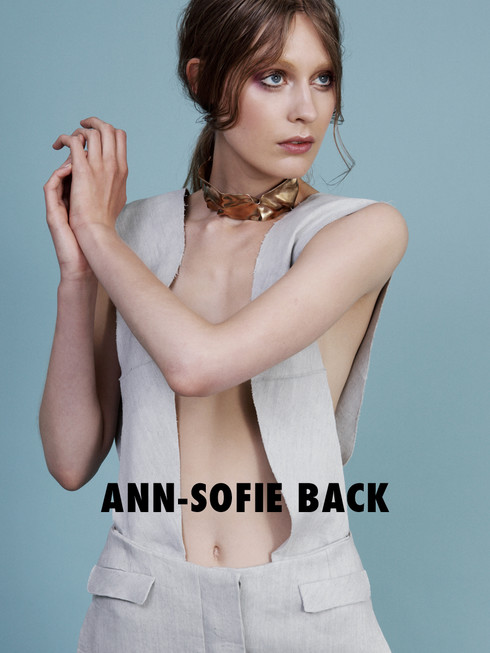

Interview with Ann-Sofie Back

Written by Mari FlorerIn front of the grey main door I stand searching for a doorbell. I can’t find any so instead, I carefully knock at the door. Nobody notices, I think. I am about to try again when the door opens.

A blonde woman lets me in. Behind the doors, down the stairs, Ann-Sofie Back stands looking up at me as I enter. Her little dog runs forward to welcome me.

“I noticed I just wrote “interview” in my calendar so I was a little bit unsure about whom I was going to meet”, she says.

I smile and introduce myself to Ann-Sofie. Then I turn to Beverly, her dog.

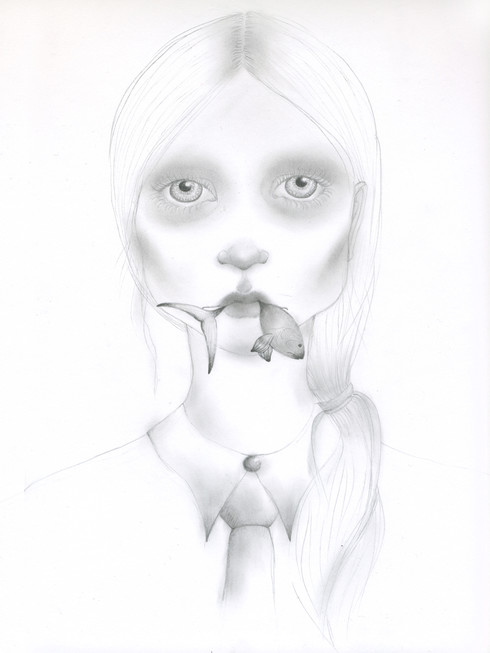

In her tiny office there are just a table and a couple of chairs. While she is out getting a cup of coffee I curiously look at the sketches on the wall.

She enters the room, sits down, arms crossed.

It is obvious that this woman has integrity, but I am not so sure that this is a trait that will make this interview an easy ride. This can go either way.

I ask her how much of her time I have.

“How much do you want?”, she asks. She’s smiling.

Ann-Sofie Back was born in Farsta and raised in Stenhamra, both suburbs of Stockholm. She tells me that her parents’ lack of interest in clothing, culture and art was a major reason why she is a designer today.

“It was a sort of revolt against the ugliness that I felt at home”, she says. “I think of it as a typical middle-class designer thing to do. To break free from all of that”.

OM: How was studying at Central Saint Martins (London) in comparison with Beckmans College of Design (Sweden)?

AB: Beckmans was very different then from what it is now. Now, it is very much better, more interesting and more theoretical than when I went there. Beckman was, strange enough, not so into fashion. At that time the common opinion in Sweden was that fashion was a bit superficial and silly. Central Saint Martins was very different culturally. Suddenly, I found myself admiring my teachers and really felt that they had a lot of knowledge.

After Ann-Sofie got her MA in Fashion Women’s Wear, she started her own label Ann-Sofie Back. At the same time she was freelancing for ACNE. She also worked for the British designer Joe Casely Hayford.

OM: What was it like, working for ACNE?

AB: It was so very long ago. I had great fun with Johnny. He really is an eccentric and special person. He chooses the people he likes and you get a lot of freedom. He has great confidence in his employees. That’s how I felt it at least when I was there.

In 2005 Ann-Sofie Back split her clothing line in two. The result is Ann-Sofie Back Atelje and Back. Back is a diffusion line.

The craftsmanship is of great importance in Ann-Sofie Back Atelje and the clothing is therefore much more expensive.

OM: Who do you have in mind when you create your clothes? If we take Back for example?

AB: I have to say the same as other brands are saying. A strong woman between 25-50. Or maybe 55. In reality our average costumer is a little bit older than we thought in the beginning. She is intelligent, knows what she wants, dresses for herself and all those things they say.

But unlike other brands that describe their customer in a similar way, the Back-woman really dresses for her own sake or for her female colleagues. She is not someone who dresses for a man. This is true also for the Atelje line. I think you must have some self distance, and it might sound silly, but I think you could not take your so-called femininity and sexiness too seriously to estimate the Back collections.

OM: Is there any artist who inspires you?

AB: No, I have not been at any art exhibitions lately. I feel quite distanced from that world. When I started as a designer it was trendy to mix art and fashion. But I think that fashion is so much more interesting as a way of expression compared to art and much more challenging to work with.

OM: So, how do you find inspiration?

AB: It is usually from things that bother me. It could be a social phenomena that I really can’t deal with or I don’t like.

One example is my collection autumn/winter 2008 who was inspired by celebrity obsession. It was a very clear phenomenon, especially in England when I lived there. They are terrible, these gossip magazines and how they hunt celebrities, and this whole misogyny. It is a very scary and weird mentality.

So I made a collection that was inspired by this. At that time the most wanted women were Amy Winehouse, Kate Moss, Lindsay Lohan and Paris Hilton. But it’s not that I think I solve any problems through my clothes. It is more like I get inspired.

OM: That brings me to another question. Are you a feminist?

AB: Yes! This whole discussion is so remarkable. Those who say that they are not feminists, do they not want to have equal pay? That’s what it is all about, if you ask me. I get completely angry with men and women who say they are not feminists.

OM: What is the best thing about Sweden?

AB: To go out with my dog without being afraid that she will get bitten to death by a pit bull terrier. It could be a really big problem in London. I did not think about it until I got a dog. In the area where I lived, it was quite dangerous. Crack house dogs everywhere who really had been trained for aggression. I was terrified every time when I was out.

OM: Do you think there is some interesting designers in Sweden today?

AB: Yes, several. There are many who are talented in different ways. I cannot pronounce their names but it is a duo that is new, Altewai anything. (Altewai.Saome) … I think they have some kind of international level on what they do.

Sandra Backlund is a fantastic craftsman, a technician that must be admired.

ACNE, it is impossible not to be impressed by the journey they have done from jeans to high-end fashion. There is no other designer who has ever done it ever before. It is an entirely new phenomenon.

OM: Is the craftsmanship just as important as the concept for you?

AB: I was not interested in that for many many years. I was very interested in the opposite. I worked with fabrics I felt lied. It looked good from afar, but when you came closer you could tell that it was knick-knacks. I wanted to reverse the luxury phenomenon.

Now when we are doing this Atelje line, of course the quality is very very important. I think it is a matter of balancing - to be smart and choose between the intellectual or aesthetic judgements.

It is probably why I admire such designers as Sandra Backlund. She is a perfectionist to the core.

When I think of the next question, I suddenly hear a snoring sound. I really can’t focus. I bend my head down to looking for the source. It is Ann-Sofies sweetheart Beverly who is sleeping on the floor.

OM: You are using linen fabric in your latest summer collection. Is it not a rather unusual or untrendy material to use today. Is this another way for you to break standards?

AB: I have used linen several times and it is just because it has such a questionable reputation. You see a certain type of women in front of you. Maybe a kind of older arty woman or librarian. That’s why I think it’s interesting, of course - to do something that I might wear in such a material.

OM: Is there anything exciting happening right now in the fashion industry?

AB: As I am also working 50% for Cheap Monday, there’s one funny thing. The jeans are back, from in fact being a bit boring for a few seasons.

Then, purely personally, it has gone amazingly well last season. I have a business partner, a great designer, and someone who take care of the economy. They all make my life so much easier compared with when I worked in London. Then, I always had the last word.

OM: Which materials do you think are coming in the future?

AB: Self-washing materials. I think it would be nice if we did not have to wash our clothes. It would also solve some environmental problems in case they found such a material. I am also very curious about what will happen with 3D printers.

I mean, will we buy clothes in stores or will we download programs and print out clothes at home? The stores will they be gone?

The power in fashion have already been taken away from the old elite and put into the hands of consumers. The bloggers caused a bit of that tradition. Maybe it is another step in some kind of democratic process. I do not know.

OM: Self-cleaning material. How does it work?

AB: I have no idea. But I’m sure it will come within a few years. I am a future freak. I think of course, that those who are under 50 today will live for several thousand years.

OM: That reminds me of Lars von Trier’s film Melancholia.

AB: I have not seen it. Is it a disaster?

OM: The end of the world.

AB: I do not believe in the end of the world at all. Everything is getting better and better all the time.